FEDERALIST 101 | Structure of Government in Expanding Societies and Removal from Novel Executive Offices | Theme and Variations

I. The Structure of Government in Expanding Societies

II. Imposing Social Rather than Systemic Coordination

III. Communist Meanings and Terms that Aren’t In the Constitution

IV. Whom did Congress give What Power to?

V. Why does a Legislature Delegate Powers?

VI. Schemes to Enforce Legislation is Not “La Séparation Des Pouvoirs”

VII. Distributed Decision-Making

VIII. Direct Accountability to Voters for Removal of Executive Officers

IX. Appropriate and Legal Powers of a Given Legislature

X. Presentment Clause is not an Adversarial or Representative Executive

XI. The Legislative Veto is not Legislation

XII. Original Textual Powers of the President

XIII. The Pragmatic Details of Offices

XIV. How does this Inform Trump v. Slaughter?

XV. Realism in Management Topology

XVI. The “Three Distinct Powers” Scam

XVII. Five-Alarm Fire of Smug Justices Spouting Nonsense

XVIII. Original Legislators did not Consciously Intend The Full Design

I. The Structure of Government in Expanding Societies

Why is what I’m about to say important to you? It’s important if you want to prevent the destruction of our civilization, by the communist impulses of its own citizens. In this case enabled by a childish comprehension of executive power, by utopian academics on the Supreme Court.

Supreme Court justices begin with common economic misunderstandings, endemic to human brain physiology. They then redefine and add eight terms in the Constitution, in an impulse to bring conscious social order to large societies. Justices have redefined two phrases, and added six terms to the Constitution, until legislation is pretended to create what they want it to create, to fit their utopian economic vision.

These phrases and terms are:

“The executive Power shall be vested in a President”,

“he shall take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed”

“entire”

“exclusively”

“administrative control”

“directly accountable to the people through regular elections”

“Separation of Powers”, and

“Montesquieu”.

To understand how these phrases are used to pervert the Constitution, we have to understand what the Constitution actually did versus what justices imagine it does. First understand that three economic properties of large societies were emerging at the time of the Constitution. These trends dictated the possible nature of any “executive branch”. Meaning whether government could be unitary like a tribe, or had to be distributed like judges and legislators.

In expanding societies at the time of the Founding:

1) All local executive officers are inescapably independent, based on the expensive economic friction of information. So that direct conscious central supervision cannot exist.

2) No executive officers are supposed to act adversarial to the legislature, which distills and disseminates the detailed preferences of society.

3) Numerous distributed checks, such as local courts and petitioners, are the only means of regulating government employees to make them delegates of the legislature.

As society expands, it subdivides. There’s no single kibbutz to supervise officers socially. And the King cannot be in the same room with every officer of government or commerce, and should not try to be. The only things it’s practical to bring together in one spot at each distributed decision-making location are:

1) domain knowledge, e.g. farming or the radio business,

2) information that expertise is applied to, e.g. local precipitation,

3) preference details of remote strangers, e.g. prices or laws, to inform officers how to use local information in a way that will benefit strangers,

4) incentives to use local information in a way that will benefit strangers, conveyed as checks by other local actors, e.g. courts and customers.

These are the economic principles of distributed decision-making, which were embodied in actual written law at the time of the Constitution. Not the unrealistic economic ideas promoted by current justices.

Justices invent nonsense arguments, to justify giving the President the power necessary for their utopian vision of a single mind operating with “the people”, such as:

1) the President is required to eradicate all crime, from which it logically follows that he must have all power;

2) the President is required to do things he cannot as a practical matter do, or in any way be compelled to do, such as directly supervise police to eradicate all crime;

3) the President’s discretion exercising personal or social priorities, is faithful execution of the law;

4) other officers aren’t independently required to follow the law, or wouldn’t be other than that they’re supervised by the President who is required to, and officers are therefore required to follow the President’s orders as the only way to have them follow the law;

5) other officers only have power to the extent the President allocates it to them;

6) discretion is necessary to execute the will of Congress upon local information, therefore the President’s discretion is necessary for local officers to execute the law;

7) creating the President excluded anyone else from petitioning in court;

8) Congress is not allowed to add details when subdividing the executive branch, so that all its expansion must have only informal social administration left up to the President to legislate, making the President a legislator of the boundaries of discretion of offices.

The Founders didn’t want an impractical king-like executive. If early legislators or politicians obtained one, it wasn’t because this is what the Constitution meant, but because the dissolution of the Constitution to obtain policy preferences began immediately. By men no more perfect than those today. Philosophical ideals and early power corrupting them were competing forces.

II. Imposing Social Rather than Systemic Coordination

The two phrases and six additions which justices use to fit the Constitution to their perceptions, all have a common theme: They imagine social coordination as if society is smaller than it is. Constantly imagining social control, competes with and corrodes the actual coordination in a large society. There is no separate or parallel path of social control by direct democracy. Chasing such control leaves local actors to crime and corruption.

It’s not that each of Madison’s departments “should have a will of its own”. They inevitably do. Is it possible in a large society for cops or legislators or judges to not have a will of their own? No. It’s that they cannot be centrally regulated to serve the will of the legislature, and must be. By accounting local compliance against the details of law, analogous to prices.

The Constitution then contrives and adds those means to distribute regulation, and does not imagine any conscious social scheme or mirage of control, beyond that which is directly specified. There’s no parallel “second vantage point” to fill in and socially regulate government employees to serve preferences, where formally-designed mechanisms do not.

A king needed to be opposed by a parliament, as observed by Montesquieu. This “separation” happened as the sensory perceptions of society became fragmented. But this did not operate in the opposite direction. The parliament did not need to be opposed and regulated by a king, except where the king added to the legislative push and pull. The legislature only needed for executive officers to do the will of the legislature. By cultivating the discretion of agents within the boundaries recorded in legislation.

In a large society, all actors inevitably act independently of any conscious will of the society. You then add systemic means to coordinate them, rather than removing conscious means to control them. Montesquieu began with a king and separated powers from him as society expanded. The United States began with a Congress, and distributed its powers to agents to act within jurisdictional boundaries appropriate to their era. In either case, separation continues as society expands. That endless subdivision is the principle written in the Constitution.

So far as Trump v. Slaughter, the Constitution never said any crazy thing like voters in Presidential elections could directly supervise the Chairman of the Federal Reserve, by electing a President for the purpose to fire him. The Constitution never said or implied, that the President could fire officers whom he did not directly work with or administrate, e.g. local prosecutors. The means for removal of officers was expiration of term, impeachment, or specific means created in new legislation. Only judges were protected from Congress creating such specific means.

If voters could see what individual prosecutors or the Federal Reserve were doing, they would want prosecutors to lie in court about people they don’t like, and want the Federal Reserve to print money and give it to them. My friend is serving life without parole for a crime that didn’t happen, resulting from this incorrect idea that voters can see what prosecutors are doing. And want those prosecutors to forfeit power to a mechanical contrivance beyond their control, by telling the truth in court.

What would actually happen if the President can legislate the behavior of individual offices, is the President will promise 50 million voters a jobs program that won’t work. In exchange for that, six of the Presidents’ friends will decide what to do with the Federal Reserve. Which policy will work worse than a Fed Chairman selected by Congress simply following the law. Which is why the Constitution calls for neither voters nor the President to directly supervise the Chairman of the Federal Reserve.

The US government has millions of employees. Its profit is in the help or harm it gives to billions of people, most not yet born. It could be decades before legislators figure out the effects of a particular law, if ever. Social accounting of the benefit of a particular officer’s activity is not possible, but only whether he followed the law.

Understand that an executive who operates like Fidel Castro, was only later imagined and written in by justices. And encouraged for the situational convenience, of those who sought immediate power to do one thing or another.

III. Communist Meanings and Terms that Aren’t In the Constitution

Supreme Court justices had to redefine two phrases, and add six terms, to pretend the Constitution intended society to be consciously directed as by a king. The two redefined phrases are:

“The executive Power shall be vested in a President”,

“he shall take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed”.

Justices redefine these two phrases unrealistically, to concentrate power in pursuit of an imagined utopian political system. To redefine these phrases, justices also added the terms:

“entire”

“exclusively”

“administrative control”

“directly accountable to the people through regular elections”

“Separation of Powers”, and

“Montesquieu”.

These terms aren’t in the Constitution, but are an attempt to add a utopian executive like Cuba.

You may have noticed that your local prosecutor never talks about “executing the law”, and doesn’t refer to his use of discretion as “the law”. You may have noticed that people other than the President, such as judges, state prosecutors, and private petitioners, act independently to enforce laws, without being “vested” with “the” executive power. And you may have noticed that imagining a single President can centrally control every government officer, doesn’t “separate their powers” but concentrates them.

Justices have redefined these phrases away from any literal meaning, in pursuit of a regressive tribal communist mirage, a so-called “unitary executive”. Where perfect information is imagined to flow freely between government employees, voters, and the President, without needing the middleman of courts and law, making the legislature obsolete.

You may also have noticed, Supreme Court justices don’t advocate for voters or Presidents to directly administrate McDonalds managers. Not just as a matter of law. But because they know that as a practical matter, central direction of McDonalds managers is impossible because information isn’t free and universal. Information problems in the real world, require a network of local distributed decision makers checking each other. In this case customers, managers, and suppliers.

But that realism where justices understand the same economic problems in commerce, doesn’t stop justices from imagining a central supervisory scheme to discover and implement the public interest, can be created using the office of President like Fidel Castro.

Justices added these terms “entire” and “exclusively” to say “the entire executive power shall be vested exclusively in a President”. Which then makes it necessary for the President to directly “administrate” local officers, rather than simply appoint them as the Constitution says. For this social process to serve the preferences of “the people” without any contact points with legislation, then requires the impractical “accountability” of direct democracy. Which would work great in a tribe of 10 people.

To make this whole system work, justices imagine we begin with a king who has unrealistic control, and then separate some specified powers from him. Which is not what the Constitution did. The United States did not begin small, with a primitive means to control officers in service of public interests, like a king. The United States began independent and adversarial. The Constitution then added means to control delegates of the will of the legislature. The Constitution did not attempt to create control by a king, where none existed, none was imagined, and none was possible in practice.

Kings began with central conscious control, which was dissolved and subdivided by the expansion of society. The United States began without any means to make executive actors delegates of the legislature, and added arms of regulation. Direct conscious regulation by a king could not be added back in, and they did not attempt to. Powers were not separated as observed by Montesquieu. They started independent, and were coordinated.

It’s because no king could inherit power over the United States, or win it in battle, that a system of distributed checks without direct social control was born.

IV. Whom did Congress give What Power to?

So what is this “the” executive power in the Constitution, if not a communist mirage of impossible supervision? What was “the” supposed to mean, in a world where people from states to individuals operate independently, and the autonomy of local actors is inevitable? This phrase was necessary to get approval and make it legal for the President to do anything, not everything.

When the Constitution said “the executive power shall be vested in a President”, it meant the executive power previously exercised by the Continental Congress. It simply meant some of the things Congress had been doing itself were now entrusted to a President, and he should take care to do what they asked of him. And specifically, in the areas of war, foreign affairs, and treasury.

If Congress called for an army, the President would hire soldiers. If Congress declares war, the President can’t say “I don’t want to go to war”.

The founding legislators didn’t attempt to create any impracticable utopian supervision pyramid, beyond offices it imagined the President could directly or closely supervise, or it would be advantageous for him to try to.

“The” executive power was the power the Continental Congress formerly wielded, or wanted to. Except they had a problem that it was impractical for them to wield it as a committee. So to solve that problem, they hired like a secretary to do their bidding. And later created other offices, to do new things beyond war, treasury, and foreign affairs.

The Continental Congress did not prosecute crime. And neither the Constitution, nor the Judiciary Act of 1789, gave the President the power to prosecute any criminal cases or choose which cases to prosecute, much less any compelled “duty” to prosecute every single one of them. That was given to the discretion of local prosecutors “sworn or affirmed to the faithful execution of his office”, and answerable to courts and impeachment. But there was no means for removal of officers except specified by Congress, or necessarily imagined by courts, only in cases where Congress left a void it did not want to fill.

What did “faithfully execute” mean? This means Congress still wanted to control what executive officers did — the choices they made — even if they had to delegate actions.

The Continental Congress did not create executive offices, because creating departments that would oppose them, was seen as beneficial for some blind religious reason of separating powers. But only to solve the practical and clearly-detailed problem, that carrying out their will needed actors in various domains. And enforcing the rules and principles decided by the legislature, upon the information of individual circumstances, had to be delegated to the discretion of local observers of those circumstances.

This did not mean all power to do everything is invested only in a President or ever can be, or that the President has the powers of a king. In a world where the average person neither voted for a President nor ever heard his voice, they certainly didn’t create a President hoping it would become a focal point for people to imagine a utopian communist political system, or inspire some vague imagination of a godlike actor knowing the needs and doing the will of the people.

The Constitution did not begin with a king who had any control, and then attempt to distribute powers away from him as necessary, like a sheriff in the Magna Carta. It began with a lack of control, and then attempted to add sheriffs and regulation where practical. Not suddenly pretend we have a king who can do all these things, and more as society expands.

They did not think a strong, independent executive was necessary to mitigate the risk of legislators becoming tyrannical. They were not driven by a religious rule that power needed to be divided among exactly three social groups. They wanted to hobble the risks of military rule, and divide loyalties everywhere.

To understand why history has no examples of a legislature becoming tyrannical, imagine if they passed a law that citizens had to send legislators their daughters to be abused. Legislators would ultimately have to send police to go get the daughters. Those police would then abuse the daughters themselves, rather than turn them over to legislators. Everyone has self interest adversarial to the preferences of society, but only executive employees can act on it. Preventing tyranny is achieved by checking and diluting executive officers, not by local executives opposing legislators.

Tyrants are not born out of legislatures, but only when they inevitably lose control of their “committee of public safety” because of inadequate checks, which becomes short-lived. A legislature could not devalue local rights and survive for very long. A legislature that doesn’t advocate for rights against abuse, is valued as a bun without a hamburger. Cops don’t need legislators to tell them to harm people.

The Founders had no problem with a tyranny of the law, because they thought they had written and would write good laws. The problem was Congress alone without soldiers couldn’t create tyranny or even enforce the law, and Congress as a group couldn’t direct an army. And so they wished to separate all the other powers that would compete with the law. So that no unitary will separate from Congress would be executed but only the law.

They didn’t wish to separate powers from the law, to have powers that operated against or independently of the law. They wished to separate all other powers and forces that would compete with the will of Congress, and thereby create an arm to execute the law. And leave all other decisions to independent parties whether states or individuals. Congress did not create some unitary collective consciousness consisting of the President and his voters and employees. Such concepts had become obsolete over history, and impossible in a large industrial civilization.

The Continental Congress did not delegate power to executive officers based on a blind religious principle that a unitary executive has value. They created executive officers for specific, practical reasons. For reasons of practical expedience to address immediate problems that were known to them. Which made executive officers a necessary evil that nobody wanted. And which were therefore divided, checked, and restrained by Congress. A tyranny of laws or legislators, was not known to or feared by the Founders.

V. Why does a Legislature Delegate Powers?

If a legislative super-majority as a single mind could collectively observe all the circumstances of society, and could supervise police action to confine all discretion to the boundaries of law, no other department would be needed. And such a supreme legislature would not be a tyranny.

Separation of powers only arises from the impracticability of such an arrangement, so that enacting and enforcing the law has to be delegated to other actors, who act not on their own conscious will but manifest the will of the legislature.

It’s only because the impracticability of the legislature acting as an eye of local observation and arm of action on numerous local circumstances, that the delegation to distributed decision makers, and the checks and balances among them by separating powers, became necessary. Making sure the executive has a will of his own, is not to oppose the legislature, but to fill in with the will of the legislature where it’s impractical for the legislature to see and act.

None of it was ever seen as a benefit of creating executives with their own will, or with any will of the voters, opposing the legislature. Voters had almost no way of seeing or speaking to government, except through their local representative. And legislators, or even superior officers, had no way to see what local government officers are doing, except through the accounting of their activities created by courts.

It was just a necessity of delegating things it was impractical for the legislature to do. But hobbling the other actors with something like the two-key system for missile launches, to prevent them becoming a force in opposition to the legislature.

And of course the legislature itself is only necessary, because the people cannot act as a single collective mind that sees everything. But rather laws are needed to optimize and transmit the boundaries of individual discretion, and cultivate a network of distributed decision makers who use what they can see for the benefit of others.

This solves the simple economic problem of optimizing division of labor, starting with a fragmented world. It’s to bring together local information, and the preferences of people who can benefit from that information, in the same place. This coordinates local actors with the preferences and activities of distant strangers.

The general principle, is not a religious belief that two powers is too small and four powers is too big. The general principle, is that as a practical matter the will of the legislature needs agents only to the extent that each is the most practical way to accomplish a task. And only in a scheme where the powers of those agents are adequately regulated, and diluted like the two-key systems used to launch missiles. There’s no general rule of power without being able to cite a practical need to create it.

There’s no magical benefit from making an executive independent from the legislature when you don’t have to. There is just an inevitability of creating local actors, to the extent the same action by a collective vote is impractical.

The separation of powers by distributing them to agents is not in itself good, it is merely necessary and inescapable. The dilution and checking of those powers is then also a practical necessity, and good to the extent it is necessary. A communist unitary executive is neither necessary nor good nor written in any general principle or specific detail of legislation.

There are no religious reasons, but only practical comprehensible and specific reasons, to delegate power to a President. The communist mirage of simply wanting a “unitary executive” to rule the world, is not a valid reason. There’s not an original principle in the Constitution that it’s important for the President to have power, for some reason that nobody can explain except through appeals to kindergarten economic illusions.

Executives separated from the President, are still separated from the legislature. Any executive actor that is separate from the legislature and regulated by the judiciary, is a separation of powers. The more separations the better. The more non-subordinate officers, the more separation of powers. None would argue that the existence of state executives who cannot be removed by the President, violates the separation of powers.

The purpose of the distribution of powers is so government employees carry out the will of the legislature, not something competing with it. The president doesn’t need to be strong, or compete with it, for the purpose of creating powers in actors separate form the legislature. The purpose of the distribution of powers is not to create a social group called the office office of President who opposes the will of the legislature.

It’s all just schemes to enforce the will of the legislature, across remote locations. It was just a practical and information problem of monitoring and supervision, given the physical friction of human interaction. Just like capitalism is a scheme to get people to use property only they know about for the benefit of others. There is no benefit to private property beyond a contrivance toward this purpose.

Nobody says the United States needs exactly one really large corporation. Law is the details of many preferences. The purpose if to spawn a proportionally vast and diverse system. Distribution of powers mean these other actors wouldn’t be executing their own conscious will or preference any more than house flippers, but would be diluted and pitted against each other in such a way, that they could only execute the numerous individual details of legislation as the systemic outcome.

Distribution of powers means that any powers other than the laws written by the legislature would be as diluted as local information is fragmented. So that no competing collective force of society would emerge. and control things toward some end other than the preferences in laws against the information at private vantage points.

Any powers to promote agendas other than or in opposition to the law written by the legislature, would be diluted out of fear. National defense would be a necessary but sequestered and divided power

VI. Adding Schemes to Enforce Legislation is Not “La Séparation Des Pouvoirs”

You cannot separate powers, which never had been and could never be whole to begin with.

Separation of powers historically — when you begin with a king or sheriff — means taking power away from the executive branch, and regulating the executive branch. So “la séparation des pouvoirs” means dividing power away from an existing king, or adding separate powers additional to a king, and regulating them with local checks conveying established preferences.

When you begin with a king, separation means adding a legislature and judiciary. This was not a law, but a crude summary of recent history. When you begin with a legislature, separation means delegation, dilution, and local checks. It doesn’t mean adding back a powerful king for some blind religious reason, without being able to explain specific practical details why, other than communist mirage and sophistry.

When you create rather than begin with a President, you don’t to separate powers from him in the traditional sense observed in history. When you begin with an ineffective Continental Congress like the United States did, you then need delegation and distribution of powers to obtain compliance. And dilution of those subdivided powers, to prevent them competing with the legislature.

The legislature and the law completely displaced the king. Then limited executives needed to be created. You subdivide agents checking each other to limit local powers and still enact the will of the legislature. When you begin with an elected legislature, you essentially need a web of tricks to get delegates to enforce the will of the legislature upon local circumstances, without forming a will of their own. The same as any king would need schemes to control his agents.

This web of tricks, and accounting for the profitability of local offices by due process rather than informal social administration, is then criticized as expensive. In the same way that banks and middlemen are criticized as parasitic in commerce, when direct regulation by a single mind is imagined as possible. Informal social administration is imagined as simpler and more powerful than it is, just by not having to specify the vague details that get from A to B, and rather assuming the conscious mind somehow takes care of all that.

Once a President is created, people imagine he could control everything. And that letting him control more would serve some values. In support of this, they point to the fact that original separation of powers had a king. They argue tradition or a snapshot of history is law, and law therefore calls for a king. Rather than making the economic argument they believe, that social administration by a collective mind is possible and efficient.

But in the real world information is expensive. And therefore regulating local actors to serve the preferences of society, requires an expensive information-transmission system. So that laborers know what to build and police know whom to harm. That economic reason is what the Constitution designed government to serve.

VII. Distributed Decision-Making

As society expands, it subdivides beyond “three distinct powers” or branches. The incentives and ambitions it’s practical or necessary to transmit, and bring together in each local node or sphere of informal social administration. are:

1) domain knowledge, e.g. farming or the radio business,

2) information that expertise is applied to, e.g. local precipitation,

3) preference details of remote strangers, e.g. prices or laws, to inform officers how to use local information in a way that will benefit strangers,

4) incentives to use local information in a way that will benefit strangers, conveyed as checks by other local actors, e.g. courts and customers.

Academics like to say “legislatorz”, “courtz”, and “the” executive branch. But there is no practical difference needing collections of legislatures checking each other to make sure laws are beneficial, and collections of local judges checking each other to act within the boundaries of law, but somehow a single social consciousness rather than fragmented knowledge among executive employees.

Legislators act independently and check each other. Judges act independently on local information and check each other to follow rules. Executive employees act independently and check each other. But based on a communist mirage, the executive branch is not imagined to be a diverse and adversarial group. The executive branch can no more be a single mind than the other branches, despite the imagined informal social operation obscuring the complex topology.

If the executive branch is imagined as a single actor contrary to the laws of physics, while courts and legislatures are imagined as collections of actors, that’s not separation of powers, and defeats the purpose of separation of powers. Not only can it not enact numerous preference details, officers will obtain a will of their own to not even enact any legislated preferences.

A unitary executive, is basically a Continental Congress of one person. Which would still have the same problem that it cannot control subordinates to administrate its will, without distributing details written in laws and checks to enforce them. But additionally would not even be representative of preferences.

You can’t just imagine that if all legislation is written by the one person rather than a committee, maybe the delegation and execution problem will go away. A unitary executive needs distributed agents and checks on them, as much as a committee does. But is lacking the preferences details to give to them. Which makes executive officers agents of the written preferences, not the will of the single executive. Which makes executive officers agents of Congress.

Take care that people do what the president wants them to do, is not the same as take care that the laws be executed. And is not a practicable scheme of supervision, because the office of the President cannot really know what local officers are doing, only local petitioners and courts can.

Phrases like “an energetic executive” manifest a disastrous communist idea of the executive branch as a single mind, while legislators and judges are understood to be multiple competing individuals checking each other. “Energetic” is just judges using a vague word because they have not much idea what they are specifically talking about. What they are talking about is discretion upon asymmetric local information, regulated to be within the boundaries of law, by proportional or mirrored checks. Not just “doing things energetically”.

There’s no vague religiously-accepted benefit from having a king or a large social sphere, or large sphere with a single money accounting, for a particular person. There’s only practical details of a particular task that dictate the most efficient domain size or economies of scale of a single actor. The domain of an actor cannot expand as society expands, but divides.

We don’t have to separate land among different owners, and we don’t have to separate powers and give some to a President. We only do this to the extent it’s the most efficient practical scheme to supervise local actors to use information only they have, to enact a preferences that are not their own. To make them act on the preferences of other consumers in the case of commerce, or of the legislature in the case of government. The contrivance is not pretty, only its results are.

A given contrivance must not be elegant, but must apply general principles in a unique way to a unique problem. There is nothing beneficial from an elegant concentration of powers in a President. But only a variety of problems to solve, and a variety of problem-specific contrivances for distributing powers, to solve them.

A solution for one problem, is not the settled law for a new or different problem. Bigger solutions and changes, just need proportionally larger majorities of legislators. Subdivision is a small problem, which might not need to be crippled by requiring super-majorities of states.

VIII. Direct Accountability to Voters for Removal of Executive Officers

Seila v. CFPB says: “The Framers’ constitutional strategy is straightforward: divide power everywhere except for the Presidency, and render the President directly accountable to the people through regular elections.”

It was equally “straightforward” that Fidel Castro would be a single conduit for the interests of the people, and equally nonsensical. No such nonsense was actually written in the Constitution or early legislation. Neither the words “entire” and “exclusive”, nor the misguided utopian ideas that promote these words, can be found there.

Not only is this not straightforward, since the President was given powers only in the areas of war, foreign affairs, and treasury. And Congress immediately created local prosecutors who as a practical matter could not also be supervised by the same single person, but rather were faithful to an oath and impeachable.

But the very idea of imagining social supervision as a single mind, is as flawed in the Untied States as it was when applied to commerce in the USSR. It’s as a practical matter impossible to concentrate power in the President without corrupting and hobbling that power, like commerce in the USSR. It’s impossible to make various activities directly accountable to “the people” by a slim margin of victory every four years. Not any more than local McDonalds restaurants could be managed by a national vote.

You literally cannot find a voter who votes based on the FCC, or a party or institution that tells them to, or a President with expertise in the radio business. Pretending individual voters can do what legislators cannot, is just a way of freeing the President to do what you want him to do.

No mechanism for how the President could directly supervise prosecutors and other officers was specified, analogous to the detailed procedures for activities such as legislation or impeachment. Because none can be specified. No such social mechanism can exist to centrally direct actors in various domains. Any effort to is corrupting and hobbling.

Just as the likes of Marx and Lenin searched fruitlessly for years, for the means to convey consumption preferences and costs through the executive branch, without private property and prices. The utopian pyramid of “administrative control” over “subordinates” imagined in Myers v. US., has been a mirage in every organization, needing rather checks numerous in proportion as there are independent actors.

The only means to convey preferences to various government officers, is laws enforced by checks more numerous than any single person or a quadrennial vote is capable of. The benefit of the subdivision of powers is that it creates a web of such checks, not an impracticable pyramid of supervision relying on trust.

Myers v. US says: “facts as to which the President, or his trusted subordinates, must be better informed than the Senate, and the power to remove him may, therefore, be regarded as confined, for very sound and practical reasons, to the governmental authority which has administrative control.”

You will remember in Seila v. CFPB, justices said officers are “directly” accountable to the people through election of the President, not mentioning this utopian middleman of “trust”. Justices didn’t advocate for removal of appointed officers by the opaque choices of “subordinates”, any more than police can search without getting warrants, or get warrants signed by a trusting sheriff. Despite police both having firsthand information and being trusted by the sheriff, who is elected by a majority. When you pull apart the arguments, it’s all just sophistry to swindle power.

There is nowhere an unlimited supply of such people that anyone can “trust” to serve the preferences of strangers. Or any single person who is able to monitor so many based on trust alone. If such trust was possible, a network of trust could have been employed in Cuba or the USSR as well as in the United States. Government operates based on mutual local checks to disseminate the will of the legislature, not trust in the virtue of others to benefit strangers with their discretion.

Justices in Seila don’t say how the voters are able to see, what in Myers the President himself cannot see, but has to “trust”. If the legislature can’t see, and the President can’t see but only trust, then certainly the voters can’t see either. And perhaps that is why no informal social procedure for removal was specified. Rather, where businessmen are brought to bankruptcy, local officers are brought to court.

Firing a prosecutor for some reason other than that he broke the law, would by definition be executing the President’s personal preferences, rather than the law. It’s impractical to enforce the preferences of society onto a prosecutor in greater detail than the written law and formal procedures can convey.

Justices understand even formal procedures for regulating prosecutors may be impractical, when they limit habeas petitions. So that local prosecutors will break the law, and often not even any defendant or court will know, much less voters or the President. A system of prisoners appealing to voters is a flawed and inefficient mirage.

IX. Appropriate and Legal Powers of a Given Legislature

“The executive power” means the President is allowed to make decisions upon information, not that nobody else is allowed to or forfeits that right. The words “vest”, “forfeit”, and “exclude” are not the same. Congress did not forfeit or exclude powers in the Constitution.

The legislature wants an energetic and intelligent mailman, not an adversarial one. If the only support for depriving Congress of a power, is a vague religious theory that an adversarial executive creates some “separation of powers” benefit parroted from Montesquieu supposedly through Madison in Myers, without critical analysis or actual legislation, that is a false theory. The only valid theory, would be that a larger majority of Congress said the particular subject matter was inappropriate for Congress.

Can a particular legislature give too much power to itself, or divide power among too many executive officers? Subdivisions of executive offices should naturally increase over time. And a legislature that incorrectly judges itself capable to undertake decisions such as war strategy, has the jurisdiction to do so if not prohibited by previous legislation of a large majority. Because there is nothing magically virtuous about any particular executive, that makes him superior in a task the legislature imagines itself competent, and capable as a practical matter, to undertake.

In a large society, the President is not certain to be a great person, as many from Aristotle to Madison and Hamilton have observed. The fact that the President is one person with few checks elected by a bare majority every four years, is a tipoff to the practical and appropriate domain of his power: very narrow.

The legislature never forfeited the power to exercise its immediate majority will. Except in contradiction to its past super-majority will. Including in contradiction to an exclusive delegation of powers granted by super-majority. The President cannot decide as adversary to the immediate will of Congress, by their own rules, and where the past super-majority is silent on the particular decision.

The absence of a judge being given jurisdiction to supervise an executive officer, does not stop Congress from supervising that officer to do something, or creating a means to make sure that officer does their will. A novel decision of an executive officer upon new material, has no special virtue that past state legislatures might demand it in preference to a simple majority of the current Congress.

X. The Presentment Clause is not an Adversarial or Representative Executive

The presentment clause makes the President a legislator equivalent to 1/6th of Congress, not an adversary of Congress. There’s a big difference between being opposed by a third of Congress plus the President, versus being opposed by the President alone. The President is adversarial only to other individual legislators in his legislative role, but immediately checked by the rest of the legislature.

The difference in representative nature of the President versus Congress, isn’t just in the bandwidth of Congress to be a conduit for and contemplate numerous diverse preferences. It’s in the ability of Congress to filter out preferences which benefit no voter. A President could order the Treasury to write him a check. A majority of Congress would not vote to write a check to a single individual Congressman.

This role of the President as legislator is important not because he better represents the public interest, but because new legislation often considers immediate circumstances which the President may have firsthand awareness of. And which the President has informed Congress of, and the need for legislation. The President knowing phenomenon-specific information for new phenomena, means the President may know what the corn looks like, not what the people want to eat.

New laws often deal with phenomena which the President may have leading-edge information about. 10 years after a law has passed, the President’s knowledge advantage about the domains of laws is likely to be less. The President providing new information on immediate phenomena, is different from the President acting in opposition to Congress on long-understood subjects long after a law has been passed, which action cannot be regulated by voters to be useful rather than corruption.

Myers v. US used sophistry to switch from the will of the legislature to individual members, when it said “the President is a representative of the people just as the members of the Senate and of the House are”. The preference of even a simple majority of Congress, is likely to be more in the public interest than an adversarial preference of the President, which in other circumstances has been estimated as equivalent to 1/6th of Congress. 1/6th would not even make the President an arm of Madison’s “stronger faction”, but corruption unchecked by voters or the legislature.

Making the President a minority legislator in new laws he may have special information relevant to, does not make it useful for the President to be an adversary of long-passed laws or of the will of the legislature in general. But this does not operate in the opposite direction. The President being useful as a legislator for new circumstances doesn’t suggest that there is harm from Congress having executive decision powers where practical.

XI. The Legislative Veto is not Legislation

More consensus is better, when it’s practical to involve more people in a decision. If Congress thinks it’s practical for a majority of the House of Representatives to decide which individuals should not be exempted from law permitting deportation, to check corruption of an office the executive branch, it’s their jurisdiction to do so. A judicial role of pardoning criminals is better invested in a house of Congress than in a single officer, if Congress thinks it’s practical. The Constitution does not demand super-majorities to decide the practicality of delegations the Constitution is silent on.

Decisions infringing individual rights need to be approved by a Senate representing minority states, and then checked by due process in court only as a practical need for process. A single house of Congress ordering a rights infringement, not supported by due process and a law passed by the other house, would be illegal. But the President alone can free a prisoner. Where the original infringement is supported by law such as in INS v. Chadha, a single house of Congress prohibiting a pardon, is checking the arbitrary decision of a single officer, not the will of the legislature.

A legislative veto is not a violation of the separation of powers, but of law and due process only in the case of infringements to the extent it is not properly regulated as executive action. A legislative veto is possibly a violation of the useful rules of a legislature itself, to concern itself with the minutia of deciding rights in unique circumstances.

But people who disagree with Congress are always going to want to make blind separation-of-powers arguments, to control and give power to the President. Because the President’s ability to act independently on local information, is proportional to his corruptibility to act on local preferences in defiance of the legislature. This idea that the executive branch needs some adversarial independence, not just to process local information but to effectively legislate with less than 51% consensus, is an invalid invention by people who want to exploit the corruptibility of the executive branch for their own values.

The challenge is at all times to get people to act in the boundaries of law, not to stop the legislature from having too much power. The excess of the legislature would be in its own ability to override minority rights, whether with or without due process. Not in their power to regulate police without needing courts, if this process as a practical matter could somehow protect rights. A bad legislature can at worst, make decisions no worse than the President himself would make, when pardoning prisoners.

Congress never forfeited unreasonably sharing a pardon power which it reasonably delegated. The President never won power on the battlefield, but only by appealing to destructive preferences and communist impulses, while pretending they are law.

XII. Original Textual Powers of the President

There is not some principle of “separation of powers” which makes it beneficial to grant unrealistic or even dangerous powers to a President. Rather there are considerations by Congress for the proper management structure and regulation for each type of office. If anything, the Constitution limited the President’s power as military commander rather than making it open-ended. Like it limited the corruption of federal judges by removal.

The Constitution enumerated the President’s social control over the military and “the” other enumerated offices, which did not include removal. When Congress created the attorney-General in the Judiciary Act of 1789, it saw a need to specifically enumerate the social control other officers would have over this officer “when requested”. Legislators saw a need to enumerate that the President could ask existing officers for written answers, grant pardons, and get legal advice from the attorney-General. If Congress didn’t enumerate these powers, some utopian vision of power of the President to even talk to other officers outside military and foreign affairs was not assumed.

This legal principle “expressio unius est exclusio alterius”, means when a law or a contract includes a specific list of items, any items not included in that list are presumed to have been intentionally excluded. The word “the” referring to “executive power” and “offices” in the Constitution, implies such a finite list of powers and offices. When legislators see the need to include something such as being able to demand written answers or remove officers, that is assumed to mean its absence would say it’s not included. Article III used the language “vested in one supreme Court”. The absence of “one” in Article II, means there is not similarly “one” executive power or office, with the President at the top of the pyramid.

Enumerating the authority of the President, to ask “the” other officers who existed at the time of the Constitution for written answers, is a very minimal enumerated administrative authority. It seems if the removal power existed, it would have implied the authority to ask officers questions and examine them. Or could easily have been specified as: “he may require the Opinion, in writing, of the principal Officer in each of the executive Departments, upon any Subject relating to the Duties of their respective Offices, and he shall have Power to remove them from their Offices”.

The President’s powers were enumerated to be specifically what powers the Continental Congress gave up or created newly in that particular office. The President is just a glorified postal secretary to deliver letters to foreign Kings when Congress orders him to. They didn’t create a President to dilute the power of the law or of Congress, by socially disseminating his own preferences.

Whatever legislators subsequently did, the most reasonable reading of the Constitution, is that Congress cannot give the President discretion over larger domains, beyond those specifically enumerated for his office in the Constitution. There was no reason for Congress to make a single person a legislator of his own values in so many discretionary domains. The Constitution set the widest scope of the President’s domain “in amber”, as limited to those powers had had when the Constitution, and anticipated legislative details, were written.

XIII. The Pragmatic Details of Offices

It’s not necessary for other officers to be picked by the President, except for practical reasons particular to each office. For an independent office like the Chairman of the Federal Reserve, there is just a need for some nominating procedure. Whatever reasons Congress had for giving nomination of officers to the President, equally for numerous offices rather than formally specifying special procedures for different types of office, those reasons and that lack of specification do not equate to specifying that the process for removing must be equal for all offices.

Extending a removal rule from one office to another office, where the principles that supported the rule no longer apply, is a trick to pursue an impracticable utopia. Allocation of powers that is not created by legislators but by judges, not based on a realistic analysis of the particular function but an imagined communist utopia, was not created by the Constitution.

The Continental Congress created the army and appointed Washington General, engaged in foreign diplomacy, and wanted a President to do these things. The Continental Congress did not prosecutes crimes. The Judiciary Act of 1789 created an “attorney-General” who served the President and other officers according to limited enumerated social control, but was not a criminal prosecutor.

The Constitution does not say “the entire executive power in the President alone” as there is no reason Continental Congress would want to do this or as a practical matter could hope to do this, with all executive activity. Congress immediately created district prosecutors.

Justices say that, as a practical matter, the President can set enforcement priorities and loosely monitor compliance with those priorities. Neither the Constitution nor judiciary Act of 1789 give the President that power, except to the extent this power is created inescapably in any nominating process. That “choosing priorities” is not “faith to the law”.

When the Judiciary Act of 1789 added district prosecutors, it didn’t say the President was going to directly administrate them, or imagine the President could directly administrate all “inferior Officers”. It did say the President was going to work directly with the “attorney-General”, who was not a prosecutor just the President’s lawyer. District prosecutors were more like local business owners, answerable to courts, local parties, and their own internal values.

Foreign affairs was specified to be an arm of the President himself. The powers of removing officers that the Continental Congress vested, did not include the power to remove offices not yet created. But was limited to Foreign Affairs, Treasury, and War. These were understood to be single activities, taken by a single actor on a single set of facts.

It could be that later Congress would want to create independent ambassadors to different reaches of the globe, answerable only to the law not the President, but would refrain from doing so for some practical reason. Not because the Constitution created a unitary inviolable power in the President.

The greatest separation of powers is achieved when the most difficult for-cause removal process is created, which must be pushed through courts or other multiple layers. Just like individual bakers serve the public interest when regulated by no senate and only the law.

Officers answer to whatever practical means are available to actually confine their behavior to the law, generally prices and courts, or other formal not social procedures. Which includes segregating their behavior from influence by some will other than the law, where it would be corruptible by politics and social forces.

Congress did not previously even try to prosecute crimes. Not to religiously separate power from them, but as a practical matter of division of labor. The judge, not the prosecutor, is the local arm executing the will of the legislature. No prosecutor can be forced to prosecute crimes his regulator doesn’t want him to prosecute, or cannot as a practical matter discover and force him to. And the legislature cannot as a practical matter be a prosecutor’s direct regulator, there is nothing they can do about it. Voters can’t stop government employees breaking the law and often wouldn’t want to, judges and non-government petitioners do.

You may notice local prosecutors never prosecute state-agenda perjury. And this enables them to serve some agenda other than the will of the legislature. Which voters often prefer, if and when they even know about it or care at all. And even when legislators add regulation to police and prosecutors, to mitigate local agendas displacing the law using perjury condoned by judges, judges just repeal it. So when voters are imagined to regulate prosecutors, which scheme is legislated by the decisions of judges not legislators, it doesn’t benefit voters.

The President was no more godlke than a commissioner of the FTC, and was essentially a commissioner of an extended set including military and diplomatic functions. Congress needed people to do all kinds of things, like deliver their mail, which is why various offices were given the title “secretary”. Every secretary was expected to “faithfully execute the law”. That did not require any secretary faithfully execute the will of any other secretary. They were requited to “faithfully execute the law” whether they had a supervisor or not.

Simply put, the Continental Congress started creating executive officers to do their will, including the President, local prosecutors, and ultimately offices like commissioners of the Federal Trade Commission. Such officers never had any power except that which the legislature created or gave up, or tragically could not control. Such officers did not separately inherit any traditional powers of kings, but only such powers as specifically given to them by legislators to do the bidding of the legislature. And such inevitable corruption as neither President nor legislature nor private petitioners can prevent.

XIV. How does this Inform Trump v. Slaughter?

So there are two questions you can ask about an executive power created by the legislature to do their will: 1) Is it necessary as a practical matter, to delegate this power by creating a new specialized information-processing actor? And 2) Is this power sufficiently checked and diluted, so as to not develop a will of its own competing with the will of the legislature?

An independent actor opposing the President but not the legislature is not a problem. Or found to be a problem, at some kind of proceeding. Removing high officers is not too complicated a problem, either for a court or the legislature. Stopping the arbitrary removal of officers being abused to corrupt government to some will opposing the legislature, is a problem.

It’s not impractical for the legislature to participate in, or make difficult, the removal of an executive officer by the President. It’s not impractical for the President to sell the legislature on why he needs to remove a particular high officer. And this is also necessary to do, to protect the interests of the legislature, including minority interests. It’s for the legislature to judge, if the legislature doesn’t think it’s impractical to use these procedures in removal of officers, to manifest their will.

The principle of the US Constitution is that everyone in government is missileers for will of the legislature. Checking the power of the President, to remove FTC commissioners and corrupt the FTC office to some will other than the legislature, serves that principle.

XV. Realism in Management Topology

The Constitution nowhere says there must be a unitary all-knowing executive, or that all powers must be purely executive, legislative, or judicial, only that they must be distributed. And mirrored with checks, as due and practical for the particulars of the office. There is no practical means of supervision by which all officers can be made subject to direct supervision by the President or voters.

The executive power is not vested exclusively in a single person, or the social group called his “office”, because it cannot be. The laws of physics prevent such utopian central planning of employee activity. Checks, balances, and supervision are inevitably super-local — meaning behind closed doors — where the only detailed remote supervision feasible is not social monitoring by remote offices and voters, but the law itself.

Attempted central planning of decisions upon individual circumstances rather than general preferences detailed in law, both hobbles the lowest officers, and turns them over to corruption like in the USSR. Regardless of whether this is practiced by a President or legislature, but more so when practiced socially by a President.

The fact that the President and Senate cooperate to appoint all officers, or calling any officer “inferior” which says no more than it can, cannot make all officers subordinate to or directly supervised by the President as a practical matter of the information limitations of supervision. Nowhere in text pretended such a utopian arrangement existed. So the utopian theory by which all action is subordinate to the supervision of the President, and by which the removal power is then justified, exists nowhere in either economic reality or text.

The will of the people was the will of the law, not even a conscious will but the preferences recorded in laws. There was not much way for the average person to have much idea what government was doing, much less know what government should do in various domains, or communicate complex information with his vote. The average person was not imagined to have any useful ideas, even if he somehow knew exactly what government was doing.

There was not much way for the average person to have a separate political relationship with the President, where he could see what the President was doing or imagine he was voting for the President to do it or not do it. It’s only with the invention of broadcast technology, that the President is able to connect with individual voters. And while people may like a powerful executive as much as they like heroin, this impulse to chase a communist mirage is un-American.

So far as “the people” supervising the President, or every executive officer in an election every four years, there’s no evidence that useful information on more than one major preference, can be distilled by spontaneous political organizations and conveyed to a single President in a single election. Exit polls characterize swing voters as having a primary issue, often at the expense of issues important to larger populations on either side.

If political parties are able to select candidates based on baskets of preferences and create platforms, that is delegation to experts by individual voters, which experts the voters then have no choice but to blindly follow. If such an informal senate is not available to consider the removal of officers, having the actual senate participate is the next best thing.

This idea of a President being elected by and representing the will of the voters he was elected by independent of written laws — independently representing the will of the people he was elected by adverse to the legislature — is a tribal regression that was invented after our Founding. At the Founding, the President was picked by a senate of legislators giving weight to minority interests.

The purpose of Madison’s departments was to filter out gathering forces competing with rather than protecting rights, not to dilute the power of the law to the values of other departments. The more departments, and the more powerless each one is except to enforce rights, the greater the separation of powers. More opposition to legislation by a stronger President is not separation of powers.

Madison never philosophized that voters could directly supervise specialist executive officers through elections. But rather that this would pervert and hobble their behavior to local corruption at best, or a return to nature by the brutal anarchy of the “stronger faction” at worst. When Madison was later advocating for an immediate agenda, he was not philosophizing on or advocating for the abstract or general principles of government, much less debating prior to the Constitutional Convention or amending the Constitution in writing.

Madison knows it’s not the conscious will of the President or any individual senator which represents the public interest, but the outcome of a process of checks and balances, legislation and litigation, creating a result consciously desired by no one. The law, as enforced by the powerless through the separation of departments, and frustrating and filtering out the conscious will of any powerful faction, represents the interests of the public. Madison knows it is the systemic result of checks and balances, rather than the conscious will of any man, that results in the law being executed.

In a different setting, Madison would have said the President is the arm of the stronger faction, united to oppress the weaker. And some due process of being checked by different departments, is instead necessary to make sure President enforces legislation, rather than his own corrupt agenda. The separation of powers was a means to filter out all other political forces — “a will independent of the society itself” but not independent of law and rights =- leaving only action within the boundaries created by legislation.

Justices religiously say we need to have a king-like figure. But they also have a practical reason. Which is either that they perceive a mirage of a collective social decision consciousness, combining government employees, voters, and the President. Or they want the President to serve some non-legislated preference.

Justices redefine and add phrases to legislation creating executive offices, based on pretending information is cheaper than it is, and therefore the ideal scale or size of the President’s domain – or of any government employee’s ideal domain size – is larger than it is. And pretending checks can be conveyed as preferences coming directly from voters through informal political processes, not legislatures and courts. Naive justices are encouraged in their communist delusions, by common political operators seeking power.

The moment the office of the President was legislated, common political operators began trying to increase its power to corrupt government to their own agenda. For the precise reason that the President cannot be directly regulated by voters, which opens his action to other interests.

The Continental Congress never tried or intended to create some utopian “unitary” collective with the voter, which cannot exist except in the minds of communist justices, or as a sales trick by those who exploit them. A “unitary executive” where voters see everything and directly supervise it by electing the President, which cannot be what the Constitution intends for the simple reason that it cannot exist, and legislators never imagined it could.

Such a system which communist academic judges claim the Constitution creates, could never serve any “public interest” as imagined. But always would be, and is, corrupted to local interests and destructive political forces. What can exist, and what the Constitution actually creates, is a distributed system and network of local checks and balances.

Of course forces immediately wanted to take power from Congress to execute their own will, and so begins the dissolution of the Constitution on the day it was born. Not unlike a child begins aging immediately, and everything dies eventually.

XVI. The “Three Distinct Powers” Scam

Just as the speed of light is the same in all reference frames, external incentives conveyed to a person are the same as laws. Whether those incentives are prices, or the prospect of criminal penalties. All decisions a person makes by then combining those external incentives with local information, is executive discretion. Anyone who attempts to transmit those incentives to a local decision-maker by deciding how the incentives interact with the local decisions, is judicial.

A prosecutor who rations his resources to enforcement priorities which he promised to voters, is engaged in a legislative activity. A legislator who begins with the need to get elected, and to write laws he can pass and get enforced consistent with the Constitution, and then attempts to write new laws within those external incentives to order judges to do new things to create some desired effect, is engaging in an executive activity in the domain of legislation.

external incentives = laws

internal preferences = legislative activity

action considering local information = executive

transmitting preferences as incentives = judicial

So buying a Big Mac for $10 is both judicial, judging the value of the Big Mac against your own preferences, but also legislative, because it transmits your likely future preferences as an incentive for a business manager to build capacity to make Big Macs, as his own executive action combining local information with external incentives.

A judge acts on written legislation. But conveying incentives in response to actions without written laws, is also a judicial function. A legislator’s executive action is to convey incentives as general laws not case-specific orders. The purpose of building a public park, is primarily executive, not judicial to reward voters as an incentive to vote for you. The delegation of domains is according to circumstances, not because roles must be purely executive, legislative, or judicial.

Myers v. US said “Removal of executive officials from office is an executive function”. But judging the activities of executive officials against values is a legislative and judicial function. Imagining voters to make this decision is a legislative and judicial rather than republican representative function. Voters are legislators and judges, then performing an executive function in the domain of voting.

Anybody who decides values, rather than just measuring values against information, is performing a legislative function. In effect adding his own legislation, which must then be accepted by anyone else he interacts with or affects. Anybody who considers specific circumstances when writing legislation is performing an executive function. Anybody who decides upon individual circumstances not directly dictated by law, is performing an executive function.

I may not want people murdered. But anyone who gets murdered, may not have the money to pay the murderer to not murder him. Government inserts a legislature and judge in place of a direct cash transaction between consumer and producer. So that I can incentivize things I benefit from, but which I cannot directly see or pay for. The law is the price, the court order is the payment. There is no practical oversized role for a President sticking his hands in every transaction. Attempts to convey detailed prices directly through the executive branch by voting, is a communist mirage.

The purpose of government can be seen as discovering preferences, and conveying them to local decision-makers. A government with millions of employees cannot as a practical matter be described as “three distinct powers”. Imagining all of society as a single interaction involving three parties, and imagining everyone as one of those parties, or even four or five or fifteen parties with one of three pure roles, is pointless nonsense. Trying to interpret law as a necessity to coalesce and purify actors, is pointless. Except to legislate your personal agenda in some office.

A government is a web of producers, consumers, and middlemen of preferences, with each actor serving multiple roles. Describing the government as at least “three distinct powers”, was designed to describe that the King did not have absolute power. t was not intended to be the final piece of legislation forming the United States government, or replace any final piece of legislation. There is no point in trying to think about government as restricted to being only “three distinct powers”, except to contrive the result of giving arbitrary power to the President in pursuit of utopia.

An unrealistic model is only promoted to market the outcome of a utopian result, while corrupting government to some agenda.

XVII. Five-Alarm Fire of Smug Justices Spouting Nonsense

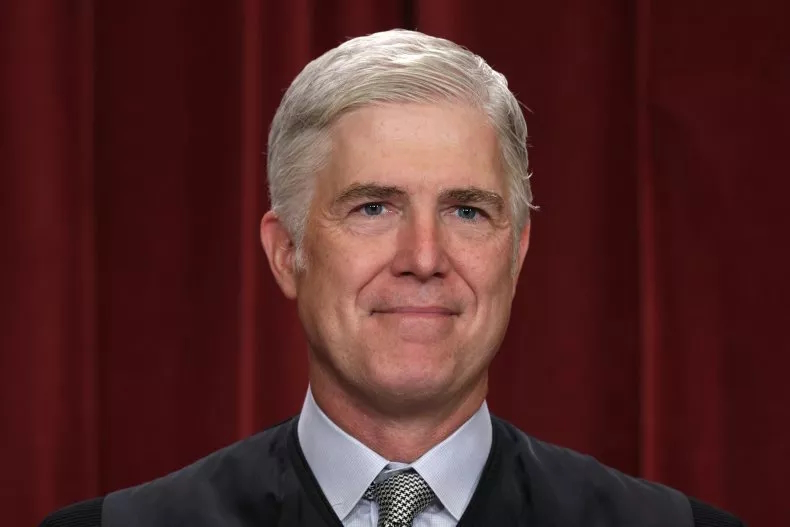

In recent arguments, justices like John Gorsuch perpetuate impossible nonsense meanings of the Constitution, like:

1) the President is required to eradicate all crime, from which it logically follows that he must have all power;

2) the President is required to do things he cannot as a practical matter do, or in any way be compelled to do, such as directly supervise police to eradicate all crime;

3) the President’s discretion exercising personal or social priorities, is faithful execution of the law;

4) other officers aren’t independently required to follow the law, or wouldn’t be other than that they’re supervised by the President who is required to, and officers are therefore required to follow the President’s orders as the only way to have them follow the law;

5) other officers only have power to the extent the President allocates it to them;

6) discretion is necessary to execute the will of Congress upon local information, therefore the President’s discretion is necessary for local officers to execute the law;

7) creating the President excluded anyone else from petitioning in court;

8) Congress is not allowed to add details when subdividing the executive branch, so that all its expansion must have only informal social administration left up to the President to legislate, making the President a legislator of the boundaries of discretion of offices.

Justices invent such nonsensical propositions as sophistry, to justify giving the President power, to fulfill their utopian vision of a communist mind supervised directly by voters. Gorsuch has not detailed any rational purpose of separation of powers, or explained why the Continental Congress would want to dilute its powers to create an impracticable and corruptible concentration of powers in law enforcement.

Nowhere has Gorsuch ever come up with a realistic definition of what “faithfully execute the law” means, except that it must mean the President is allowed to fire government employees who petition in court. Gorsuch provides no full definition of this phrase beyond that minimal definition convenient to contrive the outcome. Because there can be no full definition which that is a part of, other than in the vague communist imagination of justices.

“Faithfully execute” must refer to orders from Congress which the President has zero discretion to ignore, and can be compelled to follow. Anything else the President does with discretion, must be separate from this duty to enact the will of Congress. Except where Congress specifically allocates discretion. The natural place to allocate discretion, is to local officers who have live local information, and direct contact with parties. Their discretion is then accounted against the law by adversarial petitioners in local courts. Or other formal processes.

Put differently, a Commissioner of the Federal Trade Commissions would be required to faithfully execute the will of Congress, even if the President wasn’t required to. There is no such thing as a federal officer who is not supposed to faithfully execute the law, until and unless the President socially tells him to.

If discretion is necessary to enforce the will of the legislature upon local information, then the President’s discretion cannot be necessary for local officers to enforce the will of the legislature.

If discretion of the President exercised on local information is law, it’s still not based on local information when supervising other officers. And if the President’s discretion is independent economic rationing within the boundaries of law, then it’s not even law.

Whatever the requirement to faithfully execute the law is, it cannot be transmitted through supervision of discretion by the President, but exists independent of the will of the President. It combines law with local information, contacts, checks, and ambition of multiple parties. It is in fact the duty of federal judges, combined with the ambitions of prosecutors and defendants, to make sure federal prosecutors faithfully execute the law.

This distribution is far different from simpleton justices saying “the Founders wanted the President to do what we want, so give power to him”. It’s unlikely that justices can even follow such logic, and they certainly wouldn’t want to.

Justice Gorsuch twists the President being given specific practical powers, into saying the President has a duty to make sure that federal crimes be prosecuted, and therefore must be allowed to fire everyone. This of course has no possible rational meaning. This idea that the President is personally obligated to know of and successfully prosecute every violation of law passed by Congress without any discretion, so that he must be able to fire prosecutors not based on the President’s preferences but who don’t achieve this nonsensical objective, is just non-sequitur nonsense.

Legislators didn’t give the President the exclusive power to observe and make sure every law violation as prosecuted, not as a legislative decision, but because this would be impossible. No prosecutor can make sure every single violation of federal law is prosecuted at the expense of anything else, much lass have a duty to. And no President can as a practical matter monitor and supervise the behavior of every local prosecutor. A President cannot be compelled in any way either to prosecute any interest in court, or to send federal police to do anything.

The Constitution didn’t say parties other than the President, such as states and private parties, can no longer petition in court, that they are excluded so that now only the President can do that. A private party can petition in civil or criminal court to enforce federal law. State prosecutors have executive powers, judges can appoint prosecutors, and Congress can order testimony.