The Fragmented Utopia of Case Law

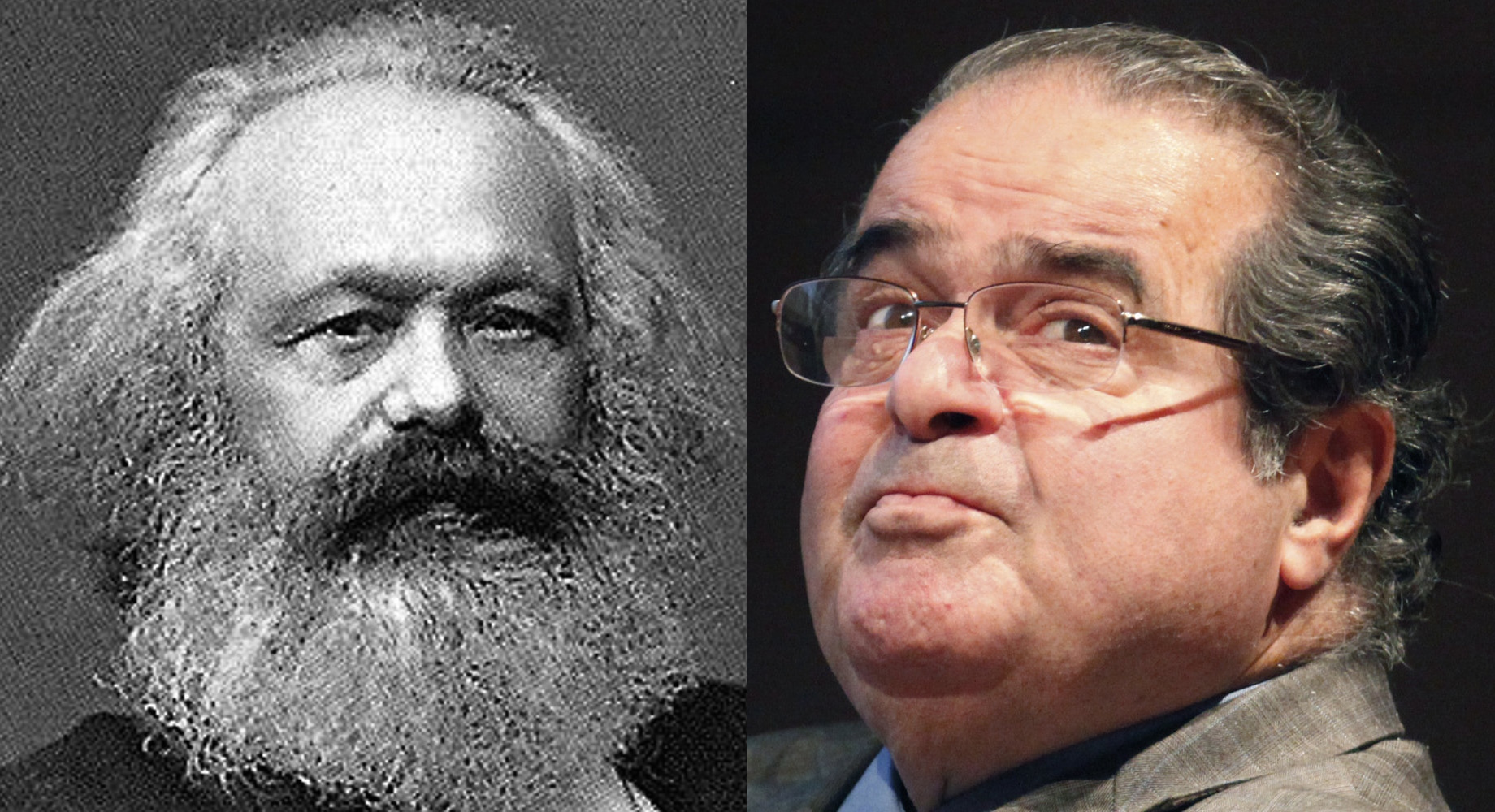

After the industrial revolution, economists like Karl Marx made heroic efforts to propose alternate systems for coordinating economic actors, other than free-market auctions. They imagined complete nations and societies, which visions were logically consistent. Even if they missed flawed assumptions permeating the entire vision. Which flaws remained difficult to grasp within their perceptions of how the world works, even after their visions had failed.

This can be contrasted against the utopia invented by judges in case law, where each judge only imagines a fragment of a utopia (though based on the same utopian and flawed assumptions people like Marx dipped into). So that if you try to piece together the various fragments of this utopia from each case, it is not even logically consistent. And nor is their utopia ever held accountable as a whole, for its poor real-world results.

For example, various fragments describing the prosecutor as an economic actor come in pieces: An assumption that he will “serve the broader public interest” if he can’t be sued in Imbler. And “we have chosen to rely on the integrity of prosecutors not to introduce untrustworthy evidence into the system” in Bernal-Obeso. Nowhere is it detailed how the prosecutor will come to do these things even if based on voters rather than prices. Or why we have juries, if prosecutors can be trusted.

Judges imagine or assume prosecutors operate based on an internal altruism (or voters are unrealistically wise), which sort of enables them to know what is true and false. Except there is not any single logically consistent explanation at all of what this nature of the elected or appointed prosecutor is. Fragments of the characteristics of this imaginary creature are only invented and introduced on the spot, as necessary to repeal law and violate rights in a particular case. These fragments are forgotten in other cases where they are not so conveniently useful, rather than joined into a coherent vision.

Nowhere does anyone try to explain the nature of this prosecutor, the way Adam Smith and Karl Marx attempted to describe the nature of the baker – his constraints and motivations – in their competing systems. Judges generally rely on assumptions far simpler and more childish than anything Marx was able to get away with, such as that human nature is good, or that the collective will is good and is informed, and somehow this is transmitted to the behavior of the prosecutor.

So that we have judges like Antonin Scalia in Hudson v. Michigan, imagining and alluding to an economic system where police don’t violate the Fourth Amendment, without being regulated by courts but rather based on “extant factors”. Without being pressed for detail on these economic mechanisms. Or Justice Gorsuch in City of Grants Pass referring to “the collective wisdom the American people possess”, without detailing what institutions other than written law conserve or propagate that wisdom.

There are academics who try to come up with more complete concepts, such as Steven Calabresi’s “Unitary Executive” or Frank Easterbrook’s “equal treatment doctrine”. But still without providing enough analysis to examine the nature of these creatures and the flawed assumptions supporting them. Such academics are constrained only by being consistent with previous words of law while trying to replace it with some utopian will of the collective. Legal academics are more pressed with not contradicting or reinterpreting previous phrases, and far less with considering and accommodating the behavior of real people in the real world.

Judges don’t need to prove to you that voters will discover and respond to misbehavior, the way economists must detail the processes by which their economic actors will respond to need and scarcity. Judges only need to show their utopia can be justified with biased and rigged word games and the simplest feel-good phrases, even as it creates unfettered executive power the same as other utopian visions.

When pressed for specifics, the best any can tell you is if the executive branch misbehaves, there will be political speech about it, and the voters can choose somebody else. If Marx proposed this same mechanism for regulating the baker or shoe maker, he would have been laughed out of town. But he would also have been ashamed of himself, unlike judges who are proud of their clever and childish little word games to create dictators.

In other words, judges proceed from the assumption that collective decision making and central planning work, and make that jive with existing phrases of law. Unlike economists who are pressed to examine this assumption, and show that collective decision making and central planning work, not play word games pretending this is what old phrases actually call for. No economist would ever be permitted to promote monarchy, based solely on a claim that is what law originally called for.

Marx created dictators unintentionally, without imagining dictators would serve the public good. Judges create dictators intentionally, based on a propaganda talking point if not a genuine belief, that elected officials will serve the public good. So they remove juries as decision makers the same as Marxists removed businessmen. Such as by saying state witnesses should be believed, when prosecutors let them out of prison conditional on saying suspects are guilty. But the same witnesses are unreliable when, for reasons other than the prosecutor coercing them, they later claim to have lied.

Courts describe small pieces of this imaginary and illogical utopia, as justifications of particular rulings. Back in the old days the government violated rights outside court. Judges have formalized contraptions by which the government can violate rights in court. They have done this using rulings based on a utopian vision of the world, quite different from the real world our Constitution and rights were designed to improve on.

Case law can overwrite law with utopia in a way designed to achieve what economists cannot, by constructing it in fragments of word games, rather than detailed economic analysis with feedback from real-world results. The utopia imagined by Supreme Court justices is held to far less scrutiny than the utopias invented by people like Karl Marx, and is better insulated against the counter-productive results in the real world.

Leave a Reply