DNA IS THE LEAST RELIABLE EVIDENCE

Radley Balko recently wrote an article on the junk science used to match people to crime scenes and condemn innocents. In the same article, Balko held up DNA evidence as some kind of actual scientific gold standard of evidence. I know two people serving life without parole for a crime that didn’t happen based on fake DNA evidence, and Balko’s statements were sadly reminiscent of the garbage coming from the stand at their trial, such as the chance someone else committed the crime being 1 in 14 billion or whatever. So let’s examine whether DNA is really so reliable.

Balko’s article documented without dispute, that there is some reason government employees want to use fake evidence to victimize the innocent. Whether it is a political incentive to appear to solve crime, whether it is for fake glory, whether they really believe they are right, or whether they are sociopathic sadists who enjoy making a mockery of the morals of jurors, is not important at this point. The question is if you begin with the assumption that they do want to use fake evidence, does DNA give them less opportunity or more opportunity?

Balko mentioned at least seven types of evidence in his article, ballistics matching, lead composition, arson mythology, DNA, hair and carpet fibers, tool and bite marks, and fingerprints. Balko’s article mentioned a case where an innocent man was likely executed for arson, so let’s look at that one first. The cited arson case rested mostly on the idea that burn marks on the floor were pools of accelerant, and that the space heater was not turned on.

Burn evidence is presumably documented in two ways, with photographs and swabs. Photographs of the alleged accelerant burns would be hard to fake. The swabs would be easy to fake, where the investigator would only need to bring his own supply of lighter fluid to the scene. But the problem then becomes one of timing. Does an investigator want to make fake swabs of lighter fluid, at a time when for all he knows the real swabs might produce an accelerant? Even worse, is it possible that they might find the actual accelerant, such as a bottle of kerosene in the suspect’s trash, which wouldn’t match the swabs?

For various reasons, the arson investigator has an incentive or is forced to produce and document real evidence, real photographs and swabs. And he is then forced to write a report based on what he has documented. And that true evidence and scientific analysis is then exposed to real scientific examination. In the case cited by Balko, a better scientist was able to use the real crime scene documentation, to arrive at a scientific conclusion that there was no evidence of arson. So arson evidence is in fact reliable.

In the cited fake arson case, it was more likely the space heater being found turned off that solidified the suspect’s conviction. Any cop who wanted fake glory could easily turn off the space heater in two seconds and then photograph it that way. Also, the witnesses of the suspect at the scene changed their stories, like they always do when the paper says someone is guilty. So the flawed arson evidence in the cited fake arson case was probably in reality more reliable than the average evidence in the same case.

Let’s consider a typical gun crime, girl found shot, boyfriend later found with gun. At the time the bullet is recovered from the scene or the victim, it seems unrealistic that a cop would already want to swap in a fake bullet. So almost certainly the actual bullet of the victim will go back to the evidence room. With that actual bullet, there is then not much benefit to produce a planted gun, as it will not match the bullet marks, and even the type of gun may not be determined by the lab with certainty for weeks. Same thing if not the gun, but simply bullets are recovered from the boyfriend’s house.

So the actual crime bullet, and actual gun (or bullet supply) go to the lab. Given both of these items have unique markings which have been documented before they get to the lab, it is tough for the lab technician to swap out either. An exception might be in the fake DNA case mentioned, where the victim was not initially known to be shot and the bullet was found days later. In that case, the police could have planted the bullet and gun after they found out the victim had a bullet wound, and they were confident no other real evidence would be found. But even in that case where everything else was faked, I believe the bullet and gun were real.

So the technician has the actual bullet and gun (or bullet supply), and then fires a test round (or takes a test sample). He then produces paper evidence documenting both sides of the match, which is then duplicated, so that a copy is retained and a copy is sent to the police or prosecutor. At the time this initial testing is done for a new crime, the technician has not much incentive to fake anything. Later on when evidence falls apart or on appeal, technicians may be put on the spot to not embarrass the government. But in most cases paper documentation of the two sides of the match will be produced and copied, before there is a practical incentive to fake anything.

At that point you have markings or chemical signatures from test and crime rounds. Any public defender is familiar with the flaws in both. So it is, as Balko suggested, a matter of what the judge lets each side tell the jury about what conclusions can be drawn from the marks. But this is not a problem of bullet evidence or physical evidence, but a problem of all testimony. Are you allowed to say a witness has a past fraud conviction? Are you allowed to say a murder victim was previously accused of rape or convicted of prostitution?

DNA is probably the worst offender so far as what you are allowed to say to the jury. You are literally allowed to tell the jury that the chance the suspect did not do this is 1 in 100 billion or something like that. The chance that this is all a dream has to be higher than that. The chance the equipment is broken and the calibration sample was faked and the lab technician is a plain liar is more than 1 in a million.

So the question is, is the difference between the real chance of error and what the jury is led to believe, greater with fibers and bullets and bite marks and whatever, or with DNA? And then what is the chance to recover from an error at jury trial, or later in the process?

The unique characteristic of DNA is it can be collected from anywhere, and match any two objects. And it is not visible and cannot be documented where you swab it, but only months later in the lab. You can collect it off a steering wheel, and match it to a hairbrush years later in another city. Carpet fibers need a carpet, bullet marks need a gun, fingerprints need a finger. All these things have constraints on how they can be produced and collected, and they usually need to be collected early in the process before a cop knows what to fake, and then they are hard documented.

The suspect and victim’s DNA can be found anywhere, weeks after the crime. A crime scene technician can wait until all the witnesses are interviewed, and all the hard evidence is logged and photographed. Then, when the police know exactly what evidence they are short, they can fake it with DNA. They can take a swab off the steering wheel of the suspect’s impounded car or his stored wristwatch, and say they got it off the steering wheel of the getaway car.

They can swap out the actual swab of the getaway car with an empty swab, or just choose to not send that swab to the lab. They can take dozens of DNA swabs from everything, and then pick and choose and mix and match which ones to send to the crime lab, versus which ones might risk exonerating the suspect. Don’t send the swab from the knife which was probably used by the new boyfriend. They can use ambiguous labels “car steering wheel” or “DNA swab of stain”, and then say which car steering wheel or which stain after they get the result.

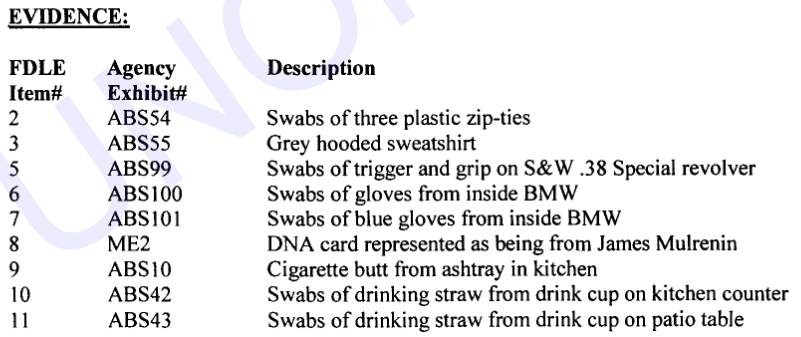

In the case I mentioned of two people serving life without parole for a crime that didn’t happen, police likely had swabs from two different sets of gloves, both labeled “swabs from gloves”. They then threw away the real set of gloves, and said both DNA swabs came from the other set, creating a fake wearer and victim. And they did not invent where they got the two swabs until two years later at trial, after they realized they had no other evidence to tie the accused to the victim. In most cases, they would at least have until after they got the DNA results back from the lab, before they would be forced at deposition to say clearly where the swabs came from.

Even the prosecutor can invent and coach the lie at trial, about where a DNA swab came from. This is important because Balko painted prosecutors as the ones selling lies in the courtroom. Is it easier to sell the jury that some stripes on a bullet are 100% unique? Or is it easier to convince the jury that some geeky CSI girl is 100% not a brazen liar, when she goes up there and suddenly says this DNA swab actually came from the suspect’s underwear on his floor not the victim’s underwear? And is there then any Supreme Court decision or case law that can stop this plain lie?

As we saw in the arson case, the greatest source of unreliability is not in the hard evidence or the probability of patterns, but in the human witnesses themselves, a cop who flips a switch on a space heater, a neighbor who lies that the suspect made no effort to rescue the children. And DNA allows the greatest opportunity for the human element to enter. And once it does, there is the least documentation of how it happened, and it is the hardest to recover from.

Leave a Reply