COERCED WITNESSES AND THE CROSLEY GREEN APPEAL (using Bayes Theorem)

I am passionate about coerced witnesses. I have watched them, I have heard stories firsthand from girls in prison. I have read about many examples, and written a lot of analysis. Coerced witnesses are basically just liars on the key details. But I have always perceived the three Crosley Green confession witnesses as more credible than coerced witnessed in general. That might be because they don’t fit into the three standard categories of coerced confession, jailhouse confession, and coerced co-defendant. So I decided to analyze what might make the Crosley Green confession witnesses more credible.

The simplest way to analyze jailhouse confession witnesses, is almost no criminals tell honest confessions to random people. The chance that a given defendant will actually confess the true story of his crime to a stranger in jail is less than 1 in 10. The number of girls in jail who know they can get out of jail by claiming an inmate confessed, and who really need it and who are dangerous sociopathic felons and professional liars, is at least 30. So you have 1/10th of a way to get a real confession, 30 ways to get a liar, the chance of a jailhouse confession being real is 1/10th to 30, or 1 in 300. The math might not be exactly right. But the principle that there are way more liars in the jail wanting to lie and get out, than criminals willing to confess and stay in, is pretty simple.

The constraints in jail are pretty low. Every girl who wants to can find out enough details of another girl’s case, to claim she confessed. Any time a girl goes to court, all the other girls can read her papers in her cell. A girl with a high bond or held without bond will have her case on TV and in newspapers in the jail. The arrest affidavit will be up on the same court website as the case of every other girl in the jail. This fits my actual experience, that most of the girls in the jail know the details of every person’s case accused of murder in the jail (and also the ones convicted of murder in the prison). Usually the only problem constraining the number of jailhouse witnesses to two or three out of the dozens who want to lie to get out, is a girl needs to be experienced enough with court cases, and also have a little luck, to design a story which fits the holes the prosecution needs filled.

There are special characteristics of the people in the jail. They are either held without bond or for very high bond cases that have not been settled yet. Or they are already convicted of something, and have no chance to win in court. So the people in jail have limited ways out, so far as winning their case. They are looking for ways other than to win at trial, which they have often already lost and are out of options. Usually girls in jail have witnesses in their own cases, and they learn a lot in the jail about testimony and lying. They know not only that they can get out simply by swearing someone else confessed. They understand the whole process, the elements of charges, depositions, where prosecution witnesses sit in court. They are practically in coerced liar college, and set up for success in lying.

Co-defendant witnesses present a little different math. There may be only one co-defendant. But that one person is guaranteed to know all the exact details of the case needed to lie and say the other person did it. That person is before trial. And the same trial strategy he would use anyway, just say the other person did it, is what will get him a plea bargain. So in any case where there is a co-defendant, there is at least a 50% chance of a coerced witness testifying against you. And as much as a 50% chance in a particular case that the one who cuts the deal is lying. Innocent people are more likely to go to trial, guilty people are more likely to take a deal. People who know how to lie and career criminals are more likely to both be guilty, and to be experienced to know how to lie to get a deal, to frame a clueless innocent person who has no idea what is going on.

So people who have co-defendants and go to trial, it is very often because their co-defendant took a deal to testify. You can argue whether the chance the co-defendant is then lying is 50%, or some other number. But the general idea is right, that people who have co-defendant witnesses will very often have coerced witnesses at trial, who will then very often be lying about key details to create the max value to the prosecution.

So it is very easy and likely for people in jail, or people who have co-defendants, to have a coerced witness who is lying. In those circumstances, it is just very convenient, there is a ready-made liar. Jailhouse confession witnesses are extremely likely to be lying, and co-defendants have a good chance to be lying in the details, or even be the person who actually did the worst crime.

Crosley Green had no co-defendant, and was not in jail when he supposedly confessed. The expected number of people who will lie about him to get a deal is much smaller. There are much fewer ways to do it. So when I said the original jailhouse confession defendant had 30 ways to have someone lie about him, and would only confess to a stranger 1 in 10 times, that does not apply to Crosley. His confession witnesses are limited to the few people he knows and interacted with, in the immediate moments after the crime. The number of people Crosley interacted with in the moments after the crime, and therefore the pool of people who can lie and say he confessed, is substantially smaller than the number of people you will be forced to live with over months or years in jail. None of those people will be quite as desperate as people in the jail who are either already convicted, or held without bond. And all of those people will be your friends, to whom you are more likely to give an honest confession.

Let’s suppose a person will be five times more likely to tell a true confession to someone he knows, than to a stranger in the jail. Let’s also suppose, the number of people you will come into contact with immediately after the crime, and who are also desperate to lie to get a sentence reduction and know how to do it, is 1/30th what it is in the jail. It is really a miracle that Crosley somehow knew or came in contact with three people who desperately needed a sentence reduction, in the short time after the crime, and not in the jail.

Using this rough math, if the chance a jailhouse confession witness is telling the truth is 1 in 300, the chance a non-jailhouse confession witness is telling the truth is 1 in 2, 50%. Even if the exact math is not right, the general idea is correct, that it is very hard to find three people willing to falsely swear you confessed, outside of the jail. It is probably easier and more likely to get the result by actually confessing. A person who is not in jail will be more likely to actually confess to people he knows, than to run into random people who need a sentence reduction and have the presence of mind and knowledge to put together a lie to do it. To hope to get to three non co-defendants outside the jail who will swear you confessed, it helps a lot and you probably need to actually confess to one of them, is your best bet of making that happen.

We can adjust that for Crosley being a freak of nature who somehow came into contact with almost as many people facing sentences as if he were in jail. But on the flip side, Crosley would be much more likely to tell a true confession to his sister, than to a stranger in jail. His sister would be less likely to testify against him than a stranger in jail. And his sister would also be less likely to testify against him and lie than a co-defendant, who needs to say the other person did it. Without a co-defendant, and including his own sister, the easiest way for Crosley to get that result is to actually confess to his sister. It is at least many times more likely Crosley’s sister told the truth, than the average co-defendant or jailhouse confession witness.

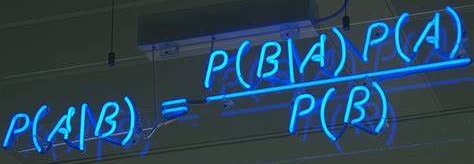

For any mathematicians, the principal that translates “ways to get the result” (such as inmates versus people you would actually confess to) into “chances the result was obtained one way or the other” (in this case with lies or with a confession), is called Bayes Theorem.

Leave a Reply