Steven Calabresi’s Idiotic New Federalist Unitary Executive

Steven Calabresi’s concept of the “Unitary Executive” relies on the same incorrect model of how society processes information, as industrial central planning and dangerous utopian movements in general.

They assume the sharing of information across vantage points is so perfect that there is in effect a single vantage point. But the problem our written laws have evolved to solve – through property rights and distributed decision-making – is that information is not perfect. And the resulting problem of coordinating independent actors to act on behalf of the benefit of others, when each person lives in his own private reality, sharing little information in common with others.

A king, a dictator, a scientist in a lab, and a person living alone in the woods all have one thing in common: They have a single vantage point at which all information is known, and from which all action is directed. From that point, the problem is deciding what to do to best benefit yourself, based on that information.

The problem then, is imagining society as this single self. If you assume the voters know everything — if voters know all resources and preferences including the values of minority voters — and if you assume the single executive can order all actions that are optimal based on that information, then anybody not acting in this chain from information to action will create a less optimal outcome.

If voters are the eyes, the collective perception is the brain, and the executive-branch employees are the arms, then of course any severing of the body will impair its function. This simplified model of the world, which might have been somewhat accurate in primitive forms of society from which we have progressed, seems to be the entire intellectual foundation supporting the “Unitary Executive”.

In reality the information known to voters collectively, the information transmitted to a President in a single election every four years, and the observations of local actions of executive-branch employees, are all fragmented and imperfect. Our form of government is evolved to overcome this problem by distributing incentives and decision-making to local decision makers, not to operate as if this information problem doesn’t exist.

Calabresi said: “a unitary executive to ensure energetic enforcement of the law, and to promote accountability by making it crystal clear who is to blame for maladministration.”

Neither what some individual government employee does, nor the effects, is ever “crystal clear” to even one voter. Not even to the wife or co-worker of the government employee, nor to a manager of a manager one level away. The government employee’s administration and its effects are certainly not detailed in the collective perceptions expressed by one candidate beating another, by 1% when elected President every four years.

Never mind that when the time comes, voters don’t even want to enforce laws, which only anticipate general circumstances with general instructions. Voters want actual specific outcomes, to the extent they can even know or monitor them. And they want those outcomes in the actual emergent circumstances as they are perceived by voters. Where what the voters even know, only arrives across an ocean of gossip, myths, grifters, political hustlers, and misinformation from demagogues. Voters then want the government to ignore law, to fulfil whatever fantasy the voters imagine.

Voters mostly know religions and witch-myths. The idea of voters knowing the details of maladministration, and transmitting those details to the President to hold him accountable, which President then directly monitors and supervises the local government employee to fix those details, is utopian nonsense.

Hayek expressed the problem as: “If we possess all the relevant information, if we can start out from a given system of preferences and if we command complete knowledge of available means, the problem which remains is purely one of logic… This, however, is emphatically not the economic problem which society faces… The reason for this is that the data from which the economic calculus starts are never for the whole society given to a single mind which could work out the implications, and can never be so given. The peculiar character of the problem of a rational economic order is determined precisely by the fact that the knowledge of the circumstances of which we must make use never exists in concentrated or integrated form, but solely as the dispersed bits of incomplete and frequently contradictory knowledge which all the separate individuals possess.”

Calabresi said: “a unitary executive eliminates conflicts in law enforcement and regulatory policy by ensuring that all of the cabinet departments and agencies that make up the federal government will execute the law in a consistent manner and in accordance with the President’s wishes.”

Sowell described the problem of a central planner monitoring and supervising subordinates as: “when Soviet nail factories had their output measured by weight, they tended to make big, heavy nails, even if many of these big nails sat unsold on the shelves… Because the central planners’ estimates of each plant’s capacity will become the basis for subsequently judging each plant manager’s success, in transmitting information to the central planners Soviet managers consistently understate what they can do and overstate what they need. The central planners know that they are being lied to, but cannot know by how much, for that would require them to have the knowledge that is missing. One way of trying to get performance based on true potential rather than articulated transmissions is a system of graduated incentive payments for over-fulfillment of the assigned tasks. Soviet managers, in turn, are of course well aware that much higher production will lead to upward revisions of their assigned tasks, so that a prudent manager is said to overfulfill his assignment by 5 percent, but not by 25 percent. In short, a mutual attempt at outguessing the other goes on between Soviet managers and central planners. Knowledge is not transmitted intact.”

All attempts at remote supervision, are destroyed by corruption to the agendas of local actors, where differences in information allow local actors to evade and trick the attempts at monitoring by their superiors. This is solved by creating independent local decision makers, who are given discretion to act confined only by some transmitted set of rules which they are incentivized to follow. And by checks between them. So that monitors cannot hope to have enough local information to decide and judge outcomes, but only to monitor whether subordinates follow the rules, by employing various independent local institutions to check each other.

It may be that a king, in a simpler civilization where all he demands is a tax in proportion to agricultural output, to finance an army to protect the border, can discover enough information to monitor and supervise his subordinates. But simply assigning this to some magic that “the voters will figure it out” – imagining that voters can perceive everything government employees are doing and communicate optimal adjustments in their choice between two candidates – is ridiculous.

Aristotle said primitive social systems are limited in size: “when of too many, though self-sufficing in all mere necessaries, as a nation may be, it is not a state, being almost incapable of constitutional government. For who can be the general of such a vast multitude, or who the herald, unless he have the voice of a Stentor? A state, then, only begins to exist when it has attained a population sufficient for a good life in the political community: it may indeed, if it somewhat exceed this number, be a greater state. But, as I was saying, there must be a limit. What should be the limit will be easily ascertained by experience. For both governors and governed have duties to perform; the special functions of a governor to command and to judge. But if the citizens of a state are to judge and to distribute offices according to merit, then they must know each other’s characters; where they do not possess this knowledge, both the election to offices and the decision of lawsuits will go wrong. When the population is very large they are manifestly settled at haphazard, which clearly ought not to be. Besides, in an over-populous state foreigners and metics will readily acquire the rights of citizens, for who will find them out? Clearly then the best limit of the population of a state is the largest number which suffices for the purposes of life, and can be taken in at a single view.”

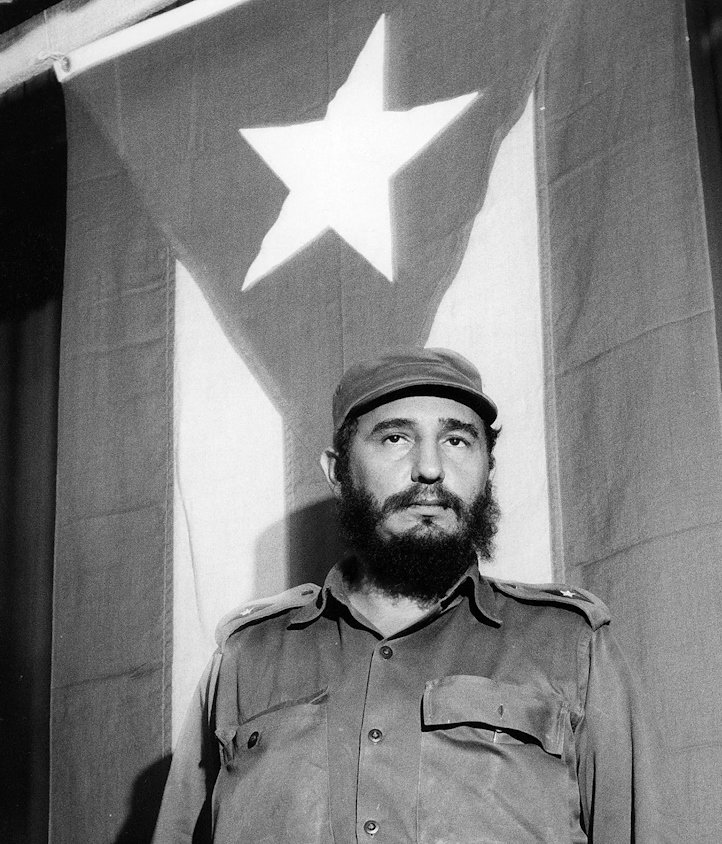

Individual voters somehow responding to local maladministration of government would require private institutions to monitor every aspect of government action, assembled together with culture and credibility that voters could rely on, like a religious organization. The private-sector apparatus that exists for this is some combination of political parties, universities, churches, think tanks, lobbyists, and the public square, which ultimately try to both monitor various activities of government and communicate to voters why the philosophy of a particular candidate is superior. The impossibility of somehow consolidating and transmitting all the necessary feedback information through a single executive is evident in the failure of planned economies under unitary executives like Fidel Castro.

It is not that Cubans don’t know they are starving, or that Castro wants them to starve, it is that information cannot be processed in the manner Calabresi idealizes. And the job of the government of conveying preferences to private decision makers as laws and regulations – as rules rather than monitoring outcomes – has become immensely more complicated after the industrial revolution, than it was in primitive agricultural or tribal society. It’s not that a new elected dictator with bolder promises could do better in the same system. Not unless what he promised, was to dissolve his power across competing decision makers.

Calabresi’s insistence that United States law requires a “unitary executive” has some basic flaws:

1) An elected President and a king do not make the same kind of decisions – the information sources and incentives measuring outcomes are different – and so no law about what a king can do has any automatic parallel in an elected President designed to be different from a king.

2) The Framers did not expect an elected President would make the same kind of decisions as a king – they did not want him to – and so did not assume every law which applied to a king would apply to a President.

3) The decision structure of a monarchy is not the best possible decision structure, and our written laws were not an anchor to such primitive forms of society but a designed progress away from them, in a clear direction to a new model of distributed decision making.

A President makes his decisions by design, based on different information and feedback compared to a king. A king has different information sources about the quality of or preference for different actions by his agents. According to Calabresi, a President is supposed to get this information from voters. (Or at least by some method of being held accountable other than courts measuring actions against laws.) And a king has different incentives compared to an elected President. The fact that a President can’t get what he wants and is interfered with and doesn’t like it — as much as a thief doesn’t like law — is the design.

So there is no reason rules useful to regulate a king, or his interaction with courts, would be useful for a President, much less legally assumed to automatically apply to a President. Particularly when we have newly designed decisions to be distributed through separation of power across independent and competing actors. A President by design has his actions regulated and limited by new and different factors, and specifically laws and courts and opposing actors.

All this intellectual malarkey was invented by the charlatans at the Federalist Society for one reason: It was believed that regulation of executives by local voters would be more virtuous than regulation by federal courts, because local voters believed in better traditional values like private property, while federal courts replaced the law with communist theories and academic fads. They believed local voters would value a better set of rights than federal courts.

But local voters and a unitary executive cannot actually enforce rights. Not without the middleman of courts and laws and numerous distributed decision-making institutions, both knowledge institutions and local information monitors and petitioners. A unitary executive cannot serve the interests of voters, but is doomed by imperfect information and control problems. Regardless of whether voters believe in private property and federal judges don’t, a system where the executive is regulated as a unitary actor by voters rather than by distributed decision making using rights and courts and laws, is Marxism.

If courts and laws are bad, then they have to be fixed and reformed. You cannot replace distributed decision making with virtuous voters and central planning. A belief in the virtue and infinite information power of local voters as deciders of everything, and that this benefit can be realized through executives immune to regulation by other checks and balances such as courts, is utopian Marxism.

For more understanding of distributed decision making, and how it manifests outside the price system in separation of powers and due process, read:

Leave a Reply